Australian and Dutch history meet at Archerfield Airport in Brisbane. During WWII this airfield played a critical role for the Dutch military who, after the Japanese armed forces occupied the Dutch colony of Netherlands East Indies (now Indonesia) to neighboring Australia. Over 20.000 people from NEI evacuated to Australia.

Poor drainage at Eagle Farm Airport, with had opened in 1925, made it unsuitable as Brisbane’s aerodrome and operations moved to a new field on 89 hectares at Rocklea which soon became known as Archerfield.

Archerfield Airport was established in Brisbane in 1931, and soon led to a strong Australian-Dutch relationship which in turn led to many friendships. The enormous enthusiasm of the people of Brisbane for the Dutch airplane De Uiver in 1934 and the farewell to the Dutch Transport Squadron in 1947 are good examples of this.

The Netherlands East Indies (NEI)- now Indonesia – was invaded by the Japanese in 1942. With the Netherlands since 1940 occupied by Nazi-Germany, the Dutch evacuated to Australia. Brisbane became the home of the NEI Government-in-Exile based in Wacol. Archerfield became the major airport for the Dutch war effort during WWII. The airport provided employment for hundreds of Dutchies and Brisbanites alike, allowing many Dutch-Australian businesses contacts to be developed.

Both on the Australian and the Dutch side, this interesting bit of history has largely been forgotten. However, the friendship and business relationships that started during that period have only grown and continued following WWII when large numbers of Dutch immigrants came to Australia. In Queensland many settled in nearby Wacol and Richmond, and 300 Dutch houses were built in Coopers Plains.

Douglas DC 2 – De Uiver

Perhaps the first important event in relation to this story took place before WWII in 1934 with the Douglas DC2- De Uiver (The Stork) airplane stopover at Archerfield. In October of that year this Dutch airplane participated in the London to Melbourne Air Race. It completed the flight in just over 90 hours, came second and was the winner on handicap. On its flight back to the Netherlands, on 3 November it flew from Sydney to Brisbane, where it arrived at Archerfield at 3pm.

The captain and KLM (Royal Dutch Airlines) pilot Koene Parmentier reported that it looked like all of Brisbane was at the airport to welcome as the news of this now famous airplane and its crew had quickly spread. There was an official ceremony at Archerfield. They were driven around in a car along rows of people who all wanted their signatures. There were radio interviews and an official dinner in town. They also received a wallaby that they promised to take back with them to The Netherlands.

The next stopover, planned for the following day, was Darwin. As they wanted to arrive there before dark, the plan was to leave at 4am. When the crew arrived at the Archerfield hangar, they were astonished to see another large crowd had gathered at that early hour to farewell De Uiver. The pilot was unable to move the plane from the hangar. A police force of ten constables had to assist the crew in getting the plane on the airfield however they were not able to control the crowd. The public had totally encircled the plane and after a while the pilot decided to start the engines while having the brakes on to create an airstream that finally saw the people moving aside and after a delay of more than an hour the plane was finally in the air. The pilot reported that because of his action “many hats were flying in the air”.

Captain Parmentier noted all of this in a book he wrote afterwards. He also mentioned that the wallaby was freely hopping though the gangway of the plane. However, the wallaby did not make it all the way to the Netherlands, because of ‘unpleasant deposits’ in the plane. They did find a good home for it at their stop in Timor.

Archerfield and the KNILM

The first air mail service

While the landing and takeoff of De Uiver was a one-off event in the Dutch-Australian history, Archerfield soon became an important hub for the Koninklijke Nederlandsch-Indische Luchtvaart Maatschappij – KNILM (Royal Netherlands Indies Airways).

Delving into the Archerfield story, it is important to provide some Dutch historical context.

Dutch East Indies Company

| The Dutch East Indies Company (Vereenigde Oost Indische Compagnie -VOC), established in 1602 became the first global corporation. They took over the lucrative global spice trade from the Spanish and the Portuguese and established many trading posts on the islands which are now Indonesia. It provided the Dutch with the wealth that was on display during its 17th century Golden Age.After the collapse of the VOC in 1799, the Dutch Government took over the VOC assets and started to fully colonise the islands. The main island was Java with the capital Batavia. The country only became officially known as Nederlands Indië (Netherlands Indies) in 1816. The VOC simply used the name Oost Indië (East Indies).

In English the country, during Dutch occupation, is nearly always referred to as Netherlands East Indies (NEI). |

At the outbreak of WWII, the colony was still of enormous economic importance to the Netherlands. At that time income from NEI accounted for 25% of Dutch GDP. This was mainly from the extraction of petroleum and minerals such as tin. The loss of this colony during WWII had a tremendous effect on the Dutch Treasury. Furthermore, the loss of the production of aviation gasoline at Sumatra resulted in severe shortages of this fuel and as such also had an effect on the allied was effort.

Because of its economic importance, there was a significant level of communications between the Netherlands and NEI. In the decades before WWII the emergence of air transport resulted in a major transformation in transport and communications.

The limited range of the airplanes in these early days of aviation, saw Australia becoming an important link in this new transport system.

In May 1931, a trial postal flight took place from Batavia (now Jakarta) to Melbourne. So far no evidence has not been found of the plane stopping at Archerfield, the range of airplanes was rather short and therefore it most likely stopped and refuelled at Archerfield. This flight of the Fokker (named Abel Tasman for this special flight), with Captain Maurits Pattist took eight days. The plane was provided by KNILM.

Bureaucratic obstacles for a regular flight service.

Following this successful test flight, negotiations started between the Dutch and the Australian Governments with the aim of establishing a regular service from London, via Amsterdam and Batavia to Australia. The flight would reduce the time it took for mail from Europe to reach Australia by some 7-9 days. It took the British Imperial Airways 17 days to fly from London to Brisbane. However, the Dutch proposals were rejected by the British Government who at that time still managed Australia’s foreign policies. It was only during WWII that Australia came into its own as a player on the global stage.

The British saw a Dutch postal service to Australia as undermining British prestige. The flight of De Uiver also needs to be looked at within the geopolitical spectrum. On the one hand the Dutch had shown that a faster service could be established. On the other hand, the Dutch success made the British even more obstructive.

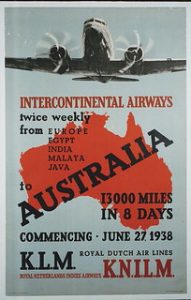

It took until 1938 before a regular passenger and mail service could be established.

In that year, the company started a weekly international flight from NEI to Australia (Batavia, Surabaya, Den Pasar (Bali), Koepang (Timor), Darwin, Cloncurry, Longreach, Brisbane, Sydney. The flight from Batavia to Brisbane cost £55 for a single ticket and £99 for a return ticket. Today’s value would be approx. $4.800 and $8.600. The Lockheed 14 carried 8 passengers. The flight took three days with two overnight stops (Bali and Cloncurry) on the way to Australia and two long days with one overnight stop (Bali).

Soon after the agreement came into force, KNILM Captain Gerson van Messel, established, a new commercial aviation record. As it was reported in the Sydney Morning Herald on Monday, 9 January 1939 he flew from Darwin to Sydney in daylight in 12 hours 12 minutes.

The article also reported the trip back. The Dutch airliner, with passengers and freight for the East and Europe, departed on Friday 6 January from Kingsford Smith airport at 5.50am and landed at Ross Smith airport. Darwin at 6.20pm local time. Its average speed was 191 miles an hour. He arrived in Brisbane at 7.21am, departed again at 8.13am, arrived at Cloncurry at 12.50pm departed from Cloncurry at 1.30pm and arrived at Darwin at 5.32pm local time.

Flights from NEI to Australia stopped once the war reached NEI in 1942. The last regular KNILM flight to Archerfield arrived on 19 February 1942. This was at the same time an evacuation flight that brought senior KNILM staff to Australia, weeks before the Japanese occupation of the NEI.

Soon after the war, resumption of the commercial KNILM service from NEI was planned, depending on the development of the political situation in NEI. Already the Dutch 19 Squadron at Archerfield (see below) had taken delivery of a Douglas Skymaster airplane from America, and two more arrived soon after that, to be used for the Indies run. These planes became a temporary nucleus for a revived KNILM service.

With the Indonesian war of independence and the subsequent transfer of sovereignty from the Netherlands to the newly formed country in 1949, KNILM fights only infrequently operated between 1946 and 1949.

How important was Archerfield for the Dutch military in WWII?

Chaotic situations surrounding the Japanese invasion of NEI

With the Japanese invasion of the Netherlands East Indies between January and March 1942, many aircraft owned by, or en-route destined for the NEI, were diverted to Australia. These involved aircraft of the:

- Netherlands-East-Indies Air Force – NEIAF (Army Air Corps of the KNIL): 19 aircraft.

- Another 24 bombers were directly ferried from the USA to Archerfield.

- Marine Luchtvaart Dienst – MLD: an unknown number of aircraft.

- Civil KNILM: 11 aircraft.

The naval and merchant fleets found themselves in a confused position. Those on their way to Java were rerouted to Australian ports as were those able to escape NEI. Many of these ships were also carrying aircraft – a total of 62. Some of these planes ended up in Brisbane (both at Archerfield and Eagle Farm Airport).

The Gulf district of north Queensland was so open to invasion that a group of Dutch vessels fleeing from NEI was able to sail down the Gulf of Carpentaria to the port of Karumba at the mouth of the Norman River before the local Volunteer Defense Corps, the sole defender of the region, became aware of them and raised the invasion alarm.

KNILM evacuation

| On the 19 February 1942, the director of the civil aviation company Koninklijke Nederlandsch-Indische Luchtvaart Maatschappij – KNILM (Royal Dutch Indies Airways) together with the wives and children from members of the senior management were evacuated to Archerfield. Other staff and their families were left behind.

This created serious anxiety among the Dutch military staff at Archerfield whose families were still in NEI. They were not allowed to fly to NEI to take them to safety. This evacuation gave the clear impression that the NEI authorities did not believe that the country could be protected from a Japanese invasion. Most of the KNILM planes were flown to Australia during February and early March, they were consequently sold to the USAAF. |

Americans arriving at Archerfield

While all of this was happening, after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the Americans had also joined the war effort and needed to get closer to the front. Australia was by far their closest ally to the front, so their massive war operation included Australia and in particular Brisbane. Between 1942 and 1944 close to one million American soldiers passed through Brisbane. From the start Archerfield played a key role in the American story as well.

At the same time the Depot Division arrived in Archerfield, the USAAF was moving its first twelve B-17Es from Hawaii to Townsville, to be closer to the advancing Japanese armed forces.

Cyclone causes alarm and damage

Lodestar LT-922 after being hit by DC-3 VH-ACB at Archerfield in 1942. Photo: via Alan BoveltBecause of communication failure at the airport in Noumea, where they refuelled, the crews of these American aircraft, were unaware of a large tropical cyclone that was on its way to Australia where it landed near Cardwell north of Townsville. Lodestar LT-922 after being hit by DC-3 VH-ACB at Archerfield in 1942. Photo: via Alan BoveltBecause of communication failure at the airport in Noumea, where they refuelled, the crews of these American aircraft, were unaware of a large tropical cyclone that was on its way to Australia where it landed near Cardwell north of Townsville.

Only two of the twelve B-17Es made it through this large tropical storm to Townsville. The other ten B-17Es of US Navy Task Force 11, diverted to Archerfield. While there was also stormy weather in Brisbane they safely landed there. On the night of the cyclone’s landfall on 18 February 1942, an Australian DC3 civilian aircraft ran into one of the B-17s while taxiing. Its brakes slipped on the wet surface of the grass runway. The DC3 also badly damaged one of the recently arrived Dutch Lockheed Lodestar, which was parked beside the American plane. The Lockheed Lodestar’s fuselage was completely wrecked and was subsequently written off. |

As both the RAAF and USAAF were short of airplanes, the NEI planes were a welcome addition. Planning for the establishment of United States Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA) had just got underway in January 1942 with the creation of a joint command for cooperation between American, British, Dutch, and Australian (ABDA) forces in the South West Pacific. While this was a financial and bureaucratic nightmare, the urgency of the war saw both remarkable, and quick decisions being made.

Netherlands Naval Aviation Service

In November 1941, the MLD had ordered 24 Vought-Sikorsky Kingfishers. When war broke out, the 24 aircraft were en-route to NEI and the ships that carried them were diverted to Australia where they arrived in March and April 1942. Of these 18 were transferred to the RAAF for use with 107 Squadron. The other six aircraft were diverted to the US Navy at Noumea.

Throughout February and March 1942 Catalina flying boats of the MLD were flown out of the NEI. On 10 March 1942 five of them were at Rathmines (Catalina Bay, Lake Macquarie, NSW). The aircraft were not transferred to Australian or US authorities and remained under the control of the MLD. In May of that year, they were flown to Ceylon to join up with other MLD Catalinas to serve as a Dutch detachment to RAF units there.

The Drama of Broome

| Of course, the hastily capitulation saw many of the Dutch in NEI using any means to get as many planes as possible, as well as ships, government archives and especially their families to Australia.The closest port of entry from Java was Broome, where many arrived in flying boats. But disaster struck when on 2 March 1942 Japanese Zero bombers arrived and within 15 minutes bombed 24 aircraft. This included the Dornier flying boats that were moored in the Roebuck Bay and other aircraft parked on the aerodrome. 35 to 40 Dutch people lost their lives and a similar number were badly injured. See the Drama of Broome.On the same day Japanese bombers attacked a flying boat that also transported a bag full of diamonds from the Dutch jewellery company, NV Handels-Maatschappij de Concurrent. The plane was shot down and crash landed on the beach of Carnot Bay (WA). To this day most of diamonds disappeared which let to investigations, conspiracy stories and lots of intrigue. |

Friendly Fire in Karumba

| In March, three Dutch Dornier Flying Boats arrived in Brisbane with Dutch and Australian refugees from the island of Ambon. They were mistakenly shot at by the Volunteer Defense Force at Karumba on the Gulf of Carpentaria when they tried to land for refueling. Luckily no one was hurt. |

Ships stranded with planes onboard

The ML-KNIL had also ordered 61 CW-22B training aircraft from the Curtiss-Wright company in the USA, of which 40 had been delivered to the NEI before the outbreak of hostilities. These were all captured by the Japanese. Another 21 were on ships en-route to the NEI but did not unload and left for Fremantle on 2 March 1942. On arrival in Australia all 21 CW-22s were handed over to the USAAF.

At the time, another 22 Douglas DB-7Bs for the Navy (MLD) were on their way on various ships to Java but were diverted to Australia where they arrived during March and April. Several of them ended up at the 18 (NEI) Squadron at Archerfield.

Another 15 aircraft had been ferried from California to Australia where they were delivered to the ML-KNIL in early March 1942. But as there was insufficient Dutch crew available to operate them, it was agreed that the planes could be repossessed by US forces in Australia later that month.

The Archerfield story of the B-25 bombers

Urgent need to replace aging planes – 162 new planes ordered

The Netherlands nor NEI and nor Australia for that matter were well prepared for war.

In NEI the ML-KNIL were using the no longer up-to-date Martin bombers (from the Glenn L. Martin Company in the USA). They were the first all-metal monoplane bombers. Rapid advances in bomber design in the late 1930s meant that these bombers, by the time WWII started, were superseded by the competition. The Martin 139-S used by the ML-KNIL in NEI could not carry enough armour and guns, nor did it have enough power to outrun the latest model fighter planes.

In June 1941, the decision was made by a desperate Dutch Government-in-Exile in London to purchase 162 B-25 Glen Mitchell bombers from the North American Aviation company to replace the Martin bombers. These new planes were in many ways superior; they could carry a payload of 1100 kg, had a reach of over 1900 km and could fly at 480 km per hour. They were to be delivered in the period from November 1942 to February 1943.

Urgent need for an earlier delivery – 60 extra planes ordered

However, because of the increasingly volatile war situation that delivery would not be in time and the Dutch Government negotiated an emergency allocation of extra planes.

The B-25 was a totally new type of plane and as other buyers took a wait-and-see-position in ordering them, the NEI was able to jump the queue and take delivery of extra bombers at reasonably short notice.

Sixty planes from a very large order of B-25 placed by the USAAF were set aside for the ML-KNIL. This batch could be delivered in early 1942. The decision was made to order these above the 162 B-25 bombers already ordered. Because of the urgency this had to be a cash sale which means it was fully paid for by the Dutch Government. The original order was still under production and that delivery was still planned to start later that year.

Planes to be delivered in British India and Australia

A ferry contract for the 60 planes (to fly the ordered planes from the USA to the destinations selected by the ML-KNIL) was signed. These planes were still supposed to be used for the war that was at that time already raging in the NEI. They would be flown to two destinations close to Java, British India and Australia.

The planning for the delivery of the first eight B-25 aircraft was: 8 in February 1942, 16 in March and 15 to 32 planes per month from April onwards. Twenty of the planes would be flown to British India via the South Atlantic route and ten via the Pacific route to Australia, where the ML-KNIL would take possession of them. Training would take place in Bangalore and Archerfield, before they would be flown to Java. The flights from the US required six refueling stops over a period of four to five days.

The B25 bombers were test-flown in Long Beach, California. From here they were flown to a Modification Centre in Memphis, Tennessee where the aircraft were brought up to date with the latest equipment. Finally, they were flown to Sacramento, California or West Palm Beach, Florida, from where they were to be ferried to the NEI.

NEI Depot Aircraft Division operation from Archerfield

In February 1942, a crew from the ML-KNIL was sent to Australia to receive the aircraft from the Americans. The largest group of NEI personnel left in four Lockheed Lodestars from Bandung. The detachment consisted of 43 people including Captain Boot, 18 pilots, 7 telegraphists and 14 mechanics. Three arrived at Archerfield Airport on 14 and 15 of February 1942.

En-route from Cloncurry to Archerfield, the third plane with Captain Boot onboard developed severe engine trouble on both engines and made an emergency landing in a meadow at Chinchilla Airport. The captain and four crew traveled by police car to Archerfield. The engines were repaired and a few days later the aircraft continued its flight to Archerfield.

Depot Aircraft Division (DVA) of the ML-KNIL was now formally established at Archerfield

The handover at Archerfield was thought to only require about a week per crew.

The plan therefor was still to fly the new B-25s from there to Java as soon as possible. The Government hoped they could still be used for the defense of NEI. By this time the Japanese had already invaded NEI (this had started on January 10) and the Japanese were now on their way to Java and the capital Batavia.

It soon became clear that the Dutch were fighting a losing battle and another ML-KNIL detachment departed from Java for Australia. This detachment, led by Major Roos, was tasked with setting up a permanent ML-KNIL organisation in Australia for the operation of the aircraft.

B-25 finally arriving in Archerfield

By late February 1942, several of the ordered aircraft were finally ready to be ferried from West Palm Beach, Florida. Two aircraft were damaged beyond repair at West Palm Beach and were not flown out.

The first three B-25 Mitchells – flown via the Pacific Route – finally arrived in Archerfield on 3 March, six days before the capitulation of NEI. Two arrived a day later and another one on 5 March.

Six planes were ferried along the South Atlantic Route to Bangalore. Eventually five reached Bangalore between 8 and 12 March 1942. One had crashed at Accra, Ghana on the way.

Regrouping after the capitulation of NEI

After the NEI had capitulated the remainder of the ferry flights were halted. The planes that were still in West Palm Beach were transferred back to Sacramento, California.

The five aircraft and ML-KNIL planes in Bangalore were transferred to the British RAF, which happened in April that year. No further planes for the ML-KNIL were sent to Bangalore. In April most of the Dutch staff was transferred to the ever-growing Dutch presence at Archerfield.

The NEI military in Archerfield were assisted by more personnel from the Depot Aircraft Division of the ML-KNIL, which had been able to move to Archerfield with Lodestar aircraft during the turmoil around the capitulation.

Enough NEI crew had now escaped to Australia enabling the Dutch to set up a new fighting squadron. As a result of this decision, the ferrying continued and a further 16 B-25 planes (part of the contract of 60 planes) arrived at Archerfield between 18 and 29 March. Some of the aircraft that arrived after April 7 were redirected to Amberley as Archerfield had become too busy. The airport had now also become the refueling station for air transport from Sydney and Melbourne to New Guinea and Darwin.

Crew’s family stranded in NEI

| The rapid invasion of NEI by the Japanese saw the Dutch crew, stuck in Australia, while their families were left behind in Java, now under Japanese occupation. Many wives and children ended up in the notorious Japanese concentration camps.Three of the NEI pilots in Archerfield were later accused of desertion as they had been planning to go back to NEI to try and bring their families to safety. |

With the urgent need of airplanes, it was decided – as was the case with the above mentioned civil KNILM planes – to sell eleven of the Lockheed aircraft to the Allied Directorate of Air Transport they were later transferred to the USAAF.

Several mishaps in and around Archerfield

| Training of the NEI pilots and technical staff started on 6 March. Just over two weeks later most of the crew was trained and ready for operation.

However, there were several mishaps and accidents which happened mainly with some of the ferry pilots during that initial period: · Two planes were damaged during a landing exercise. In the end two B-25 planes were written off. One plane with factory problems was used for spare parts and the other damaged planes were eventually repaired, Because of the slippery grass surface at Archerfield two other planes from the USA were directed to Amberley where there was a hard surface runway. |

Detachment ML-KNIL Archerfield

Later 24 more B-25s arrived from the USA. The by now 50 men strong group of ML- KNIL personnel became known as Detachment Archerfield.

Finally in March 1942, the USAAF withdrew the priority assignment of the B-25s to the ML-KNIL and instead decided that:

- 18 aircraft were to stay or to go to the ML-KNIL in Australia;

- 24 were to go to General MacArthur for the USAAF in Australia;

- 5 were transferred to the RAF in India;

- 6 were retained by the USAAF for delivery to Brazil; and

- 4, still at the Memphis Modification Centre and were retained by the USAAF.

This accounts for 57 aircraft – three others had been written off.

Twelve of the planes allocated to General MacArthur were taken over by Lieutenant-General George Brett who became the Commanding-General of the Allied Air Forces in the South West Pacific Area. These planes were urgently needed for the 3 Bombardment Group of the USAAF, because its crew had arrived at Archerfield – but without aircraft.

The 18 Netherlands East Indies Squadron

It was the intention of the commander of the ML-KNIL General van Oyen to establish a NEI Squadron using the various aircraft and air crew who were now at Archerfield this included Dutch technical personnel who had been able to evacuate to Australia. Collaboration with the RAAF led to the formation of a combined squadron.

The 80 ML-KNIL members from Archerfield together with members of the RAAF now formed the 18 Netherlands East Indies Squadron. These airmen were divided into several operational groups under RAAF control. All their stores and equipment were supplied by the American Armed Forces.

A few months later under a similar arrangement between the Dutch and Australian military command a second squadron was installed, named 12 Squadron. This squadron moved from Archerfield to Merauke in the southern part of Dutch New Guinea – the only unoccupied territory in NEI.

As the busy Archerfield airfield was not suitable for the training of the Dutch crews, the 18 Squadron was transferred to Canberra, in April 1942.

Captain Boot received the boot

| General van Oyen wanted to make Captain Boot provisional squadron commander until the whole squadron would reach operational strength.However, Boot was very unpopular among his staff. They accused him of ill treatment and a lack of respect, this nearly led to a revolt under the NEI crew.General van Oyen decided to instead appoint Major B.J. Fiedeldij to take over the command.

Boot apparently did change his behaviour and returned at the Squadron as an Operations Officer and became a highly decorated pilot at the 18 Squadron. |

After their training in Canberra, the 18th became operational and was moved to McDonald Airfield near Darwin. This was closer to the battlefield. The squadron was now brought to full strength with the arrival of more RAAF personnel and consisted of 40 officers and 210 men from the ML-KNIL and 8 officers and 300 men from the RAAF.

They were involved in many actions across NEI and were operational until 1950, when the equipment from the squadron was handed over to the Indonesian Airforce.

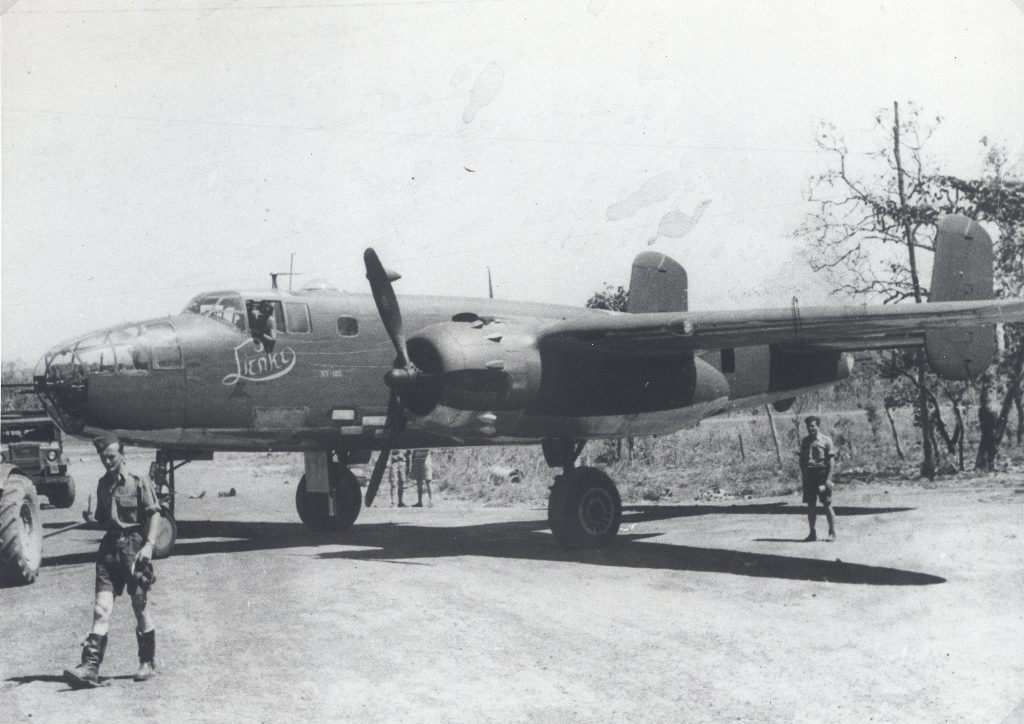

The Forgotten Story

Lienke’ the B-25 Mitchell flown by Gerson Hagers of the 18 Squadron NEI at Potshot WWII airport in WA. The plane is named after his wife, who he had to leave behind in Java. Source: Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie.One of the greatest pilots of the Squadron was Gerson Hagers. He was also one of the original pilots who was stuck at Archerfield and could not bring his wife Lienke to safety. Unknowingly to him she ended up in a Japanese Camp.He wrote a war diary that also details the revolt against Boot, the drama with his colleagues who wanted to fly to NEI to pick up their family and the politics of the NEI Government and military, the latter was often not very flattering. A novel has been written based on this period of his life titled: Het Vergeten Verhaal (The Forgotten Story). Gerson had never really been able to re-adjust to life after his after his demobilisation. He emigrated to the United States where he found work as a ‘crop spray pilot’. In 1952, he died in Oregon in an air crash while at work. Lienke wrote her own memories which have also been included in the book. She later remarried and lived in California as Linda Duncan-Buriks. Lienke’ the B-25 Mitchell flown by Gerson Hagers of the 18 Squadron NEI at Potshot WWII airport in WA. The plane is named after his wife, who he had to leave behind in Java. Source: Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie.One of the greatest pilots of the Squadron was Gerson Hagers. He was also one of the original pilots who was stuck at Archerfield and could not bring his wife Lienke to safety. Unknowingly to him she ended up in a Japanese Camp.He wrote a war diary that also details the revolt against Boot, the drama with his colleagues who wanted to fly to NEI to pick up their family and the politics of the NEI Government and military, the latter was often not very flattering. A novel has been written based on this period of his life titled: Het Vergeten Verhaal (The Forgotten Story). Gerson had never really been able to re-adjust to life after his after his demobilisation. He emigrated to the United States where he found work as a ‘crop spray pilot’. In 1952, he died in Oregon in an air crash while at work. Lienke wrote her own memories which have also been included in the book. She later remarried and lived in California as Linda Duncan-Buriks. |

This ends the story of the B25s and that of the formation of the 18 Squadron until their departure from Archerfield. The plan was to establish a second NEI squadron, however, because of staff shortage this didn’t happen. In December the 120 NEI Squadron was formed in Canberra.

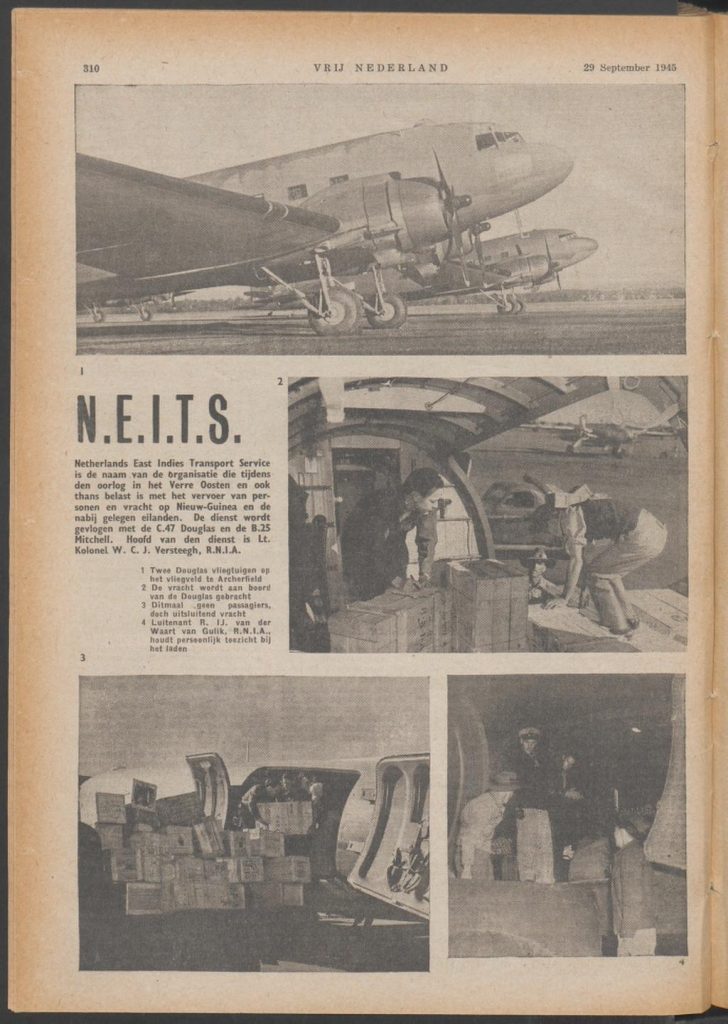

The next stage of the Dutch history at Archerfield now moves to the NEI Transport Afdeeling Brisbane (NEI Transport Section Brisbane – NEI-TSB).

NEI Transport Department Brisbane

Transport and communications aircraft were much in demand in Australia due to the vast distances that had to be covered between the various fields of operation (mainly in the north of the country).

In January 1943, the NEI-TSB was the first air transport service formally established after the capitulation.

The Section administered initially eight pilots, four aviation wireless operators, a second pilot-air gunner and eight flight engineers of which three to be cross-trained as second pilots. All were former civil KNILM and KLM personnel evacuated to Archerfield. Following the capitulation of the allied forces in Java they continued to work for the KNILM for about one-and-a-half-month operating charter flights within Australia. By May however they all had ended up jobless because the company ceased operations when their planes were sold to the Americans.

Consequently, they were seconded to the ML-KNIL and became the core of the new Transport Section (TSB). The NEI-TSB was equipped with three Lockheed Lodestars and five B-25 Glen Mitchell´s.

They became a flight unit of the USAAF especially attached to the 39th Troop Carrier Squadron (TCS) and the 317th Troop Carrier Group (TCG) USAAF both stationed at Archerfield.

NEI-TSB – special services unit for General MacArthur

| From February 1943 onwards, the Dutch were asked to operate daily night courier flights between Archerfield and Port Moresby. General MacArthur, who was headquartered in, what became the MacArthur Building in the CBD of Brisbane, requested the services of the Dutch to courier reports backwards and forwards between these two destinations.These night flights were not without danger, and MacArthur had stipulated that they needed to be operated by volunteers. The whole NEI TSB crew agreed to take on that job and the operation remained exclusive to them. The operation did not have one single incident during their one-and-a-half-year of operation! |

NEI-TSB were also tasked to undertake transport flights in USAAF Douglas C-47 Skytrain planes within Australia and ferried men and material to 120 Squadron in Merauke (later on to Biak also in Dutch New Guinea) and the above mentioned 18 Squadron at Batchelor (NT).

The work of the NEI-TSB dramatically increased with the formation of the NEI Government-in-Exile in neighboring Wacol.

NEI Government-in-Exile

Most members of the NEI Government had been able to flee to Australia and had organised themselves in Melbourne. Following hastily established diplomatic relationships in January 1942, the Australian Labor Government offered the Dutch almost unlimited support in relation to facilities and training, while at the same time providing them with a remarkable high level of independence for their operations in Australia.

They were unable to regroup in the Netherlands as the home country was under the occupation of Nazi Germany. The Dutch government was also in exile, headquartered in London.

The NEI Government-in-Exile was formed in April 1942. This was the first, and only time, that Australia hosted a government in exile.

Some 20.000 Dutch people arrived in Australia during February and March 1942.

In the chaos of those days before the capitulation the various Departments of the NEI Government including the army, navy and air force became scattered across Australia. Communication and travel between the various offices became increasingly more difficult and time-consuming once they became more organised

When it became clear that liberation of NEI was coming within sight, the decision was made to prepare for the return to NEI. For a return after the liberation, consolidation was urgently needed, so in 1944 it was decided to centralise the various headquarters of the NEI organisations to “Camp Columbia “at Wacol in Brisbane.

The Americans had built Camp Colombia in October 1942 and in April the following year it became the headquarters of the US 6th Army. However, General MacArthur’s headquarter was moved to a new base at Hollandia, Dutch New Guinea once it was liberated in June 1944.

Wacol now became the Dutch headquarters. Situated across Ipswich Road from the Wacol railway station, Camp Columbia comprised of offices, barracks, accommodation huts and an internal road network.

Archerfield now became an important airport for the NEI Government-in-Exile.

NEI Government-in Exile fundraiser for the Red Cross

| On 18 July 1945, the NEI Government-in Exile held an Indonesian Night at the City Hall Brisbane as a fundraiser for the Red Cross. The function was attended by many Dutch and Australian employees from Archerfield Airport. |

1 NEI Transport Squadron at Archerfield

In September 1944, after the regrouping of the various Dutch headquarters in Camp Columbia in Wacol, NEI-TSB merged with NEI-Transport Section, Melbourne (NEI-TSM).

Because of their increase in size after the merger, as well as its increased importance being the main transport unit for the NEI Government-in-Exile, the combined sections became an official squadron, known as the 1 NEI Transport Squadron (NEI TS). At the start, 16 Dutch Dakota aircraft were stationed here and operated also with civil and RAF crews. The aircraft strength was expanded with four Douglas C-47 Skytrains and five Lockheed 12 light transport planes. The USAAF had largely left Archerfield due to the transfer of their units from Australia to Dutch New Guinea, leaving room for the expanded Transport Squadron. An extra 100 civil engineers were recruited in Brisbane to assist with the increase in activities. Repairs and maintenance of NEI TS aircraft were also undertaken at Mascot, Sydney and in Wagga Wagga.

The transport squadron operated flights for the NEI Government-in Exile, in support of the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration (NICA) who was in charge of food aid and housing recovery for the local population. They also supported the Netherlands Forces Intelligence Service (NEFIS).

Further assistance was provided to the battalion headquarters of the KNIL, its subordinate units in Casino (NSW) and the KNIL companies and detachments of guides/interpreters operating with the allied ground forces in New Guinea. The flights to destinations in New Guinea were the main task of the unit.

At the first stage of the Borneo campaign in 1945 the Squadron supported the 26 Australian Brigade at the Battle of Tarakan, the Australian Brigade also included a KNIL infantry company. This was an important event for the Dutch as this was for the first time since the capitulation in 1942, that a unit of just KNIL personnel participated in the fight against the Japanese. While the Allied forces won the battle, its overall success in relation to loss of lives and costs was questionable. However, the Allies were now able to advance for the first time towards Java and the other islands of the Archipelago.

Steel plates had to be installed by the Engineering Corp on the beach of the island, allowing the planes to land safely – a remarkable and dangerous exercise.

Diplomatic incident

Their was a minor diplomatic incident between Australia and the Netherlands. In March 1945 five women of the Darja Collin Dance Troupe touring the Allied Forces had left from Archerfield Airport, Brisbane to Merauke in Dutch New Guinea to entertain the troops.

The Australian Director-General of Security noted in May 1945 that the three women had travelled without passports and exit permits. When questioned at Archerfield the Dutch Liaison Office had stated that they were three ‘Dutch Army Nurses’. When interrogated on their return the security note states that ‘The story was a complete falsehood’.

The Deputy Director of Security of Queensland was ordered to inform the Dutch authorities that they will no longer be permitted to proceed to Dutch New Guinea unless they are in the possession of passports and exit permits. (Source Documents in the National Archives of Australia).

19 (NEI) Transport Squadron – after the War

Coincidentally, on the same day of the surrender of Japan on 15 August 1945, the Squadron was renamed 19 (NEI) Transport Squadron.

The Japanese surrender

| After the two atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August and the Russian invasion in Manchuria on the 8th of that month, the Japanese finally agreed to a surrender on August 15th. The Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers Douglas MacArthur demanded the Japanese to fly to Manila to discuss the conditions for the surrender, but he did not directly participate in those negotiations. This event known as the Manilla Conference was attended by Australian, Dutch, and other Allied officials. The formal surrender was signed by MacArthur and the Japanese, was only signed on 2 September, on the USS Missouri in the Bay of Tokyo.19 Squadron played a small role in the preparations of the surrender of Japan. On 21 August Captain Gerson van Messel flew Lt Gen L.H. van Oyen, the acting Commander General of the KNIL to Manilla, in a Douglas C-47 Skytrains rom Archerfield. He attended the conference on behalf of the NEI Government-in-exile.The pilot was the same Captain Gerson van Messel who in 1939, had set the above mentioned aviation record with his passenger’s flight from Darwin to Sydney. |

With war over, the 19 Squadron now began flying to destinations in the Dutch East Indies and Dutch New Guinea. Transport requirements massively increased as an estimated 200.000 NEI and allied PoWs and civilian internees in concentration camps in the NEI, needed food and medicines as they were on the brink of starvation. An estimation that soon proved to be far too low.

To be able to manage this enormous task all transport aircraft of 18 Squadron were, in February 1946, transferred to the 19 Squadron, as well as aircraft from the MLD. The Squadron became the executing agency of the NIGAT (Netherlands Indies Government Air Transport). This required even more aircraft and more personnel at Archerfield.

Staff were both recruited in the Netherlands and Australia and new planes were ordered, Canada was also able to assist here. After the arrival of the final batch of three Douglas C-47 Skytrains and a C-117/DC-3D from Canada in October 1946 the Squadron had a total strength of 47 Dakotas. Most of the training took place on the Amberley Airfield in Brisbane.

With the situation in NEI slowly improving, planes, staff and material were gradually moved to Kemayoran Airport at Batavia (Jakarta). However, this became increasingly more difficult and complicated as the Indonesian people wanted to end Dutch colonialisation and were fighting for independence. They were supported in this struggle by Australian Trade Unions who blockaded maritime transport from Australia to Indonesia. The boycott did not include air traffic and this created extra pressure on the air force. Occasionally however also air transport became involved in the boycott.

In July 1946 the Dutch launched their euphemistically called ‘Police Action’ against the Indonesian freedom fighters. In his book Black Armada, the author Rupert Lockwood mentioned the extraordinary following event.

“A RAAF officer in Brisbane said that after the Police Action the Air Force had been instructed not to supply petrol to Dutch planes. The officer added that this instruction came from the RAAF Headquarters in Melbourne and applied ‘for the moment’. The ban grounded three Dutch planes at Archerfield aerodrome, Brisbane”.

It led to political turmoil as it was questioned in the Australian Parliament if the RAAF was under the control of the Government or the trade unions.

Indonesia gained independence in 1949 after a bloody war of independence against the Dutch. Australian mediation and diplomacy played a key role in this process.

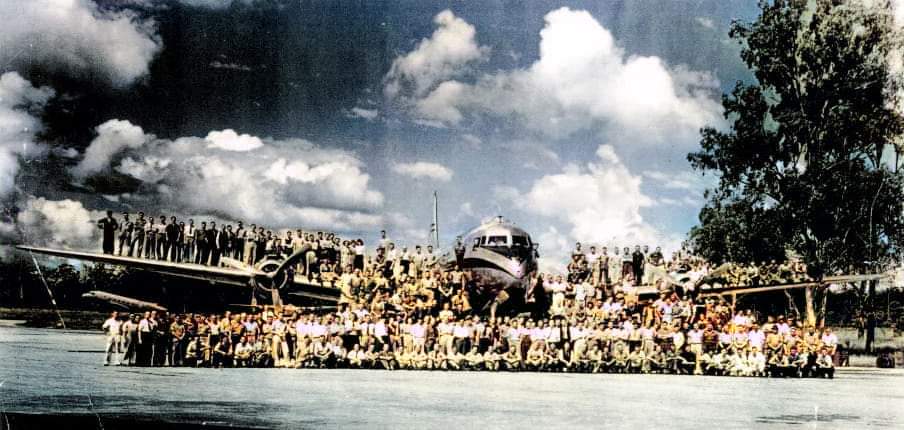

19 Squadron officially farewelled Archerfield in early 1947, where this most amazing picture was taken. On top of one of the Dakotas is the Dutch staff with their family members. At ground level are staff members of Archerfield Airport.

James Saunders, somewhere in the picture above.

| James was an engine fitter in the RAAF during WW2. He served at Birdum (NT), Ambon (Indonesia) and finally in PNG fixing tank engines for the Australian Army as they had aircraft engines in some of the later model tanks.He was discharged at the end of WWII and worked at Archerfield for the Dutch Air Force (NEI Transport). When the NEI Transport Squadron departed Archerfield for (what is now) Indonesia they offered James a job in NEI, as most of the Dutch nationals at Archerfield wanted to return to the Netherlands after six years isolation in Australia. He declined this offer, as well as an offer from the USAAF to relocate to Guam working on their aircraft.This information was provided by James’ son Graham Saunders (July 2021) |

This doesn’t seem to be the end of the Dutch at Archerfield as later in February 1947 a Dutch DC3 crashed in Moreton Bay.

ML-KNIL Dakota crashed in Moreton Bay.

| A ML-KNIL Douglas Dakota caught fire and crashed into the ocean about 23 minutes into a test flight from Archerfield, killing all six people – three Dutch servicemen and three Australian crew members – onboard.Parts of the plane were recovered in 2015 however, the fuselage, including the bodies of the crew, has not been located.An article from the 27 February 1947, in The Courier-Mail quoted police who said the plane crash landed in 60 feet (18 metres) of water.The plane’s location would not qualify as a Commonwealth War Grave, owing to its demise having occurred in peacetime, nor would it qualify for protection under the Historic Shipwrecks Act as it is not yet 75 years’ old. |

When no 19 squadron – now located at Batavia – was abolished on 1 April 1948, all remaining aircraft were handed over to 20 Squadron.

After the war, many Dutch people from NEI migrated to Australia. This was very much encouraged by the Dutch government as they tried to get as many of the Dutch immigrants from NEI to move to Australia. The Netherlands was just coming out the German occupation and had enough problems of its own.

The 300 Dutch houses build in Coopers Plain, very close to Archerfield Airport, is a good example of the continued relationship between Australia and the Netherlands.

Paul Budde

Brisbane 2021

A special word of thanks to Dr Peter Boer in the Netherlands who generously allowed me to use his detailed research on the military air force history of the ML-KNIL during WWII

Dutch Sources:

In drie dagen naar Australië

Het 18 Squadron N.E.l. van april tot en met december 1942

Het Vergeten Verhaal

http://shyamahopman.blogspot.com/2015/02/Het-vergeten-verhaal-van-een-onwankelbare-liefde-in-oorlogstijd.html This is also translated in English: Finding Her (https://www.amazon.com.au/Finding-Her-Charles-Den-Tex/dp/9462380783)

Begrensde Horizonten

Other sources:

ML-KNIL Air Transport Units 1943 – 1946 – https://www.dutchavia.nl/index.php?start=1

Netherlands East Indies Air Transport units of the Militaire Luchtvaart KNIL – Dr. P.C. Boer

Early NAA B-25C Mitchells of the ML/KNIL, February 1942 – June 1942 – Dr. P.C. Boer

Refugee, stranded and evacuated aircraft of the NEI Army Aviation Corps in Australia and British India – Dr. P.C. Boer

Sunken wheel rekindles 1940s Straddie aircraft mystery.

Black Armada, Rupert Lockwood – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rupert_Lockwood